How to Make Scenario Planning Stick

Developing future scenarios can deepen leaders’ strategic insights. Establishing scenario planning as an ongoing capability and reaping its full benefits require linking it to other processes.

Topics

News

- Waymo Secures $16 Billion to Expand Robotaxi Operations Worldwide

- OpenAI, Snowflake in $200 Million Deal to Embed AI in Enterprise Data

- Musk Merges SpaceX and xAI in Deal Valued at $1.25 Trillion

- TASC Group Appoints New CEO To Lead AI-Driven Growth in the MENA Region

- What Is Moltbook? A New Social Network Built for AI Agents

- OpenAI May Secure $50B From Amazon in Ongoing Talks

With managerial anxiety rising in step with economic, geopolitical, and technological uncertainty, scenario planning is of increasing interest to executives seeking to be prepared for what they cannot yet see. But while there is much to learn by envisioning a wide range of possible external scenarios, many organizations fail to fully absorb and integrate these lessons into strategic decision-making.

Scenario planning is a good starting point for navigating uncertainty in business. As one of us (Paul) explained in these pages 30 years ago, the strength of scenario planning is that it goes beyond extrapolating known key trends to contemplate major uncertainties that companies do not fully understand yet.1 Scenario planning assumes that an organization’s future environment may be markedly different from what it is today due to external forces, including political, economic, social, technological, environmental, or legal developments. The art and science of scenario development involve examining the most important of these drivers, exploring their potential developments, and modeling how they might interact to create vastly different futures. Testing multiple scenarios lets leaders assess the robustness of their strategies and prepare the organization for new threats and opportunities. As Louis Pasteur put it, “Chance favors the prepared mind”; mentally mapping out future-scenario narratives positions managers and organizations to benefit from as yet unseen developments.

If done right, scenario planning can be an important strategic component in managing a rapidly changing world in timely ways. But scenario planning by itself is seldom sufficient to yield this benefit for a variety of reasons. We argue that the key to success is to support scenario work with complementary practices, such as employing adaptive strategies, monitoring external change, and fostering a learning culture. These requisite organizational capabilities — augmented by agile management, savvy decision-making based on real-time information, and farsighted leadership — serve as crucial connective tissue for integrating scenario planning into business operations. When well connected, these elements become integral pillars of state-of-the-art strategic management in turbulent times.

Here, we will describe in more depth the set of practices that includes and extends scenario planning to help organizations prepare themselves to parry new threats and seize new opportunities. But first, we shall look at some examples of isolated scenario practices to explain their limitations.

Why Scenario Planning Alone Is Not Enough

Many leaders who set out to practice scenario planning have found sustaining it beyond an initial start challenging. Consider the following pertinent examples we know firsthand.

Shell’s famous initial scenario project, circa 1970, yielded prescient global energy scenarios that were ignored. They were developed by a small group of central planners in London that did not involve enough top leaders. This omission proved particularly painful because one of the scenarios anticipated the tripling of oil prices following the Arab-Israeli War in 1973. Having learned its lesson, Shell’s subsequent scenarios were owned more by senior leaders and had far deeper impact, even if they were perhaps less brilliant or farsighted. But eventually, it took much more than senior support for scenario planning to take root within Shell: It required training, coordination, and a redesign of the company’s overall business planning system.2

Another recent example concerns a major U.S. transportation company project related to the future of electric truck transport. The scenario-building exercise generated many spirited discussions among the senior managers in the work group. But there was clear reluctance among team members to formally present their futuristic visions to the C-suite because the scenarios felt overly speculative. As one senior engineer put it, “We are trained to argue our case with evidence and data, while our scenarios, although plausible in our own views, may come across as fiction rather than solid future planning.”

The planning team at a municipal utility providing water to a sizable U.S. city offers another example. The team had developed diverse scenarios about water’s future demand and supply. But much of that good work fell on deaf ears because most operational managers did not know what to do with the scenarios they were handed. When, 10 years later, another such scenario exercise was proposed in support of the utility’s goal of carbon neutrality by 2050, there were few takers. Scenario planning did not fit with the organization’s strong operational culture. In academic lingo, there was not enough absorptive capacity and connective tissue in the organization to internalize and leverage a powerful tool to creatively envision future threats and opportunities.

Opposition to scenario planning is sometimes akin to the human body reacting to a foreign invader by boosting the immune system. Organizations, like other complex systems, may instinctively try to reject changes that move them beyond their natural comfort zone. These countervailing forces can take many forms and may depend considerably on context, culture, leadership, or more. As history shows, these forces can be strong.

A Compass for Navigating Uncertainty

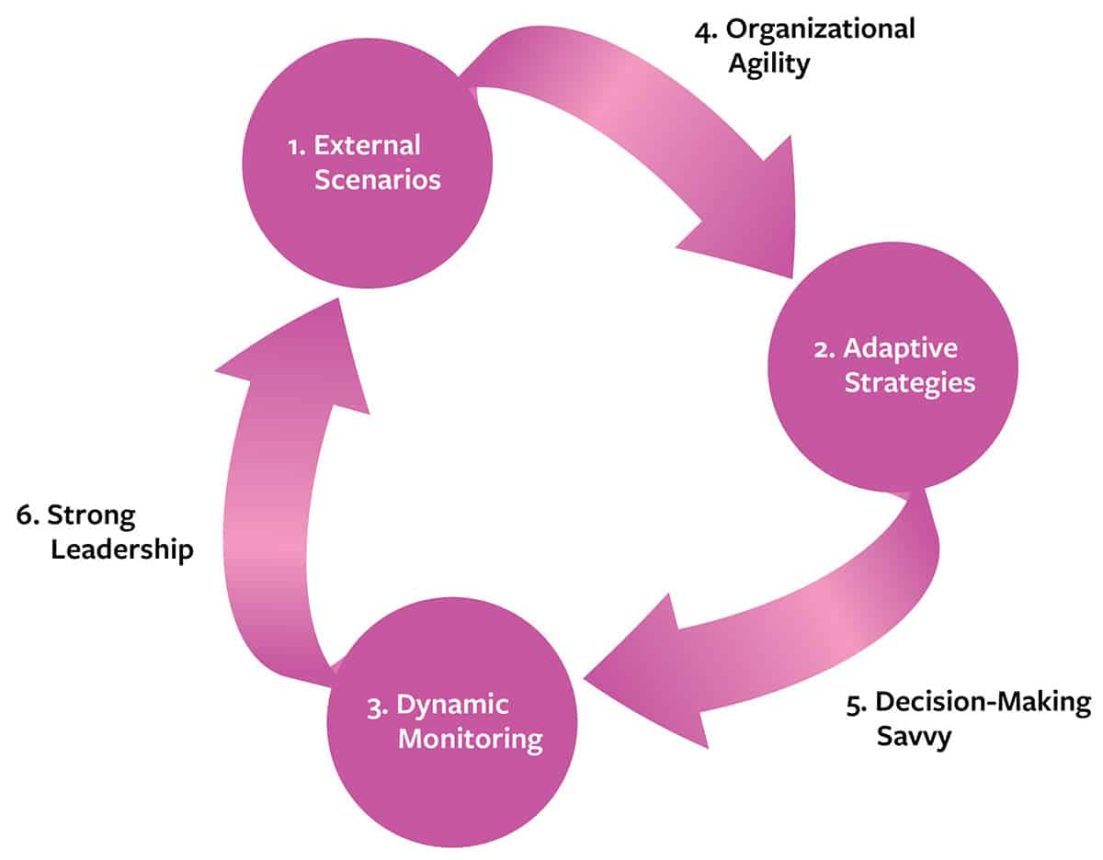

Employing five practices along with scenario planning can help build the kind of connective tissue missing in the cases above. Together, they arm leaders with the tools to manage rising uncertainty effectively.

- Use multiple scenarios to improve your organization’s insight and foresight about the future, with due respect for what is still unknowable.

- Devise adaptive strategies that have sufficient flexibility built in to deal with the unexpected, including future-proofing your plans using real-options thinking.

- Employ dynamic monitoring to track the external world in real time when updating scenarios or executing strategies and plans.

- Improve organizational agility, in terms of structure, processes, norms, and rewards, to cope better with unexpected change.

- Foster decision-making savvy to implement and adapt various plans and strategies in smart, timely, and coordinated ways.

- Cultivate strong visionary leadership at multiple levels in the organization to deal with crises and other unexpected exigencies more effectively.

To illustrate how these six approaches help leaders navigate organizational uncertainty, consider how pilots rely on state-of-the-art aircraft engines, maps, radar systems, and well-trained crews to handle midcourse adjustments. Scenario planning is analogous to using an aircraft simulator to prepare airline pilots to handle uncertainty. The aim is to experience a wide range of contingencies and be mentally prepared to respond well when needed. Adaptive strategies prepare leaders to deviate from the original plan when necessary, similar to how pilots rely on ETOPS for access to emergency landing options at nearby airports.3 ETOPS — Extended-range Twin-engine Operations Performance Standards — sacrifices the shortest geodesic path between locations in return for safely landing a two-engine aircraft in case one engine fails. Although such adaptive strategies may not be optimal in stable environments, they are important when people are faced with unexpected scenarios, either in the air or in business.

Dynamic monitoring of the business environment is akin to pilots’ use of radar systems and radio signals from planes ahead of them to stay updated about weather conditions. Pilots maintain a wide safety margin around a plane so that they can move up, down, or sideways when encountering unexpected turbulence or flying objects. Likewise, leaders who maintain organizational agility have the freedom to deviate from a plan. Additionally, information flows and decision-making need to be aligned for clear communication about changes to the current plan, similar to how pilots coordinate with air traffic controllers and issue updates and instructions to the cabin crew and passengers. Last, strong leadership is critical in both organizations and aircraft, with clear protocols and lines of communication in place to ensure that collective responses to unexpected signals or events are effective. (See “Six Elements to Navigating Uncertainty Using Scenario Planning.”)

Six Elements to Navigating Uncertainty Using Scenario Planning

The circles represent the three core practices that should be in place as part of a robust approach to managing uncertainty via scenario planning. The arrows represent capabilities that serve as connective tissue to support and strengthen the core and help leaders integrate insights gained from scenarios into their decision-making.

1. Use multiple scenarios. The first step of our framework is about exploring multiple futures for a given business, including how adjacent sectors may evolve. Leaders must select an appropriate time frame and define the relevant scope in terms of regions, technologies, and business arenas. The time frame and scope will typically exceed a company’s current planning horizon and business footprint. The aim is to examine a range of key uncertainties and distill them into a few internally consistent narratives that tell relevant stories about different futures that may lie ahead. Later, these scenarios can be refined for tactical decisions or operational issues. But first, different future visions will need to be shared and debated.

Developing macro scenarios upfront has multiple benefits. First, it invites leaders into a dress rehearsal about different futures before they occur. This helps prime the organization to recognize weak signals about impending change sooner. A second benefit is that the scenarios encourage contingency planning, which helps future-proof the strategy through stress-testing. A third key benefit is that scenario planning may challenge leaders’ most deeply held strategic assumptions, which is crucial whenever mental models are rigid or outdated. Last, broad-scale scenario narratives allow for a common language and shared learning about the future. Offering managers a common, richer vocabulary will lead to better discussions about future possibilities, warning signs, and strategic choices the business faces. Also, exploring diverse views of the future emphasizes that no single right answer yet exists about the organization’s direction and that a diversity of opinions is needed and will be respected.

Scenario planning may challenge leaders’ most deeply held strategic assumptions, which is crucial whenever mental models are rigid or outdated.

Consider the example of chemical producer Alchemy, which applied scenario planning to formulate and implement its supply chain strategy for the Asia-Pacific region circa 2011.4 Alchemy developed four different scenarios and then stress-tested its current supply chain strategy for robustness against them. Its leaders then identified initiatives that could succeed in multiple scenarios and prioritized their implementation. The scenario exercise also alerted managers to subtle changes in the business environment, such as economic slowdowns in China. An evaluation conducted in mid-2014 confirmed this: Implementations of initiatives that worked well in most scenarios had advanced smoothly, while those suited to only one of the scenarios were being suspended. Scenario planning can be thought of as creating surrogate crises to avoid real ones and energizing an organization to change.

2. Devise adaptive strategies. The aim is to develop strategies that do not lock the organization into a decision but instead allow it to maintain prudent flexibility. Organizations can garner more flexibility by developing a broad portfolio of strategic options to place many small bets. In addition, they can use contingent contracts, hedge investments, or engage in other forms of financial risk management to maintain flexibility. Suppose that adding a new plant is a brilliant move in a scenario of high growth but foolish in a recession scenario. Flexible strategies may include building the plant in stages, signing contracts to offload excess capacity if needed, using multiple work shifts if demand is high, and perhaps forming strategic partnerships to share some risks.

The essence of an adaptive strategy approach is to balance “no regret” moves (which can be strongly committed to since they make sense in every scenario) with carefully crafted flexible investments that amount to “call options on the future” (when uncertainty is high). And if making partial investments is not possible, some really big bets may still have to be made — such as investing over $10 billion in a semiconductor fab. But in that case, the scenarios should help assess more fully the risk-return trade-offs they entail.

At first, adaptive strategies may look inferior in terms of net present value or the urgency to act, and thus they may get rejected in favor of more rigid strategies premised on just one view of future. But when leaders broaden their perspective to include different possible futures, it can change this thinking. For example, after contemplating four freight logistics infrastructure scenarios with long planning horizons, senior transportation experts changed their initial recommendation. Earlier, they had strongly favored immediate implementations of large infrastructure projects, but the scenarios led them toward flexible approaches, such as allocating funds to specific regions and strategically staging some big projects.5

The basic idea behind options thinking is to pay a small amount upfront to get in the game, wait until some key uncertainties become clearer, and then decide which options to commit to more fully or pull out of. This real-options perspective, in contrast to market-based financial options, underpins adaptive strategies for investments that are not market traded. Real-options thinking can be formalized into a disciplined managed system via decision trees, Monte Carlo simulations, Bayesian updating, and value-of-information calculations.

3. Employ dynamic monitoring. The monitoring system here concerns the external macro environment and complements executive dashboards that measure internal progress or the local business environment. The scanning metrics tracked typically measure the larger context outside the sphere of an organization’s control, such as growth in gross domestic product, geopolitical risks, the number of patent applications, and so on. These indicators should be tailored to the scenarios as well as to strategies of the company so that they function as an integrated early warning system. The better metrics are leading indicators that foreshadow how external events may change the business environment. A simple example is measuring rainfall high up on a mountain to predict flooding in the valley below later. Well-known business examples of leading indicators are the Purchasing Managers’ Index and jobless claims. More specialized ones might track new patent filings to foresee disruptive technological innovations.

The better metrics are leading indicators that foreshadow how external events may change the business environment.

Some of the best indicators may be privately sourced ones rather than public metrics, since the latter are more readily arbitraged in markets. But these private ones may require subjective judgments by seasoned managers, expert panels, or even prediction markets created specifically for this purpose. Continued advances in IT, AI, and external monitoring will produce far more sophisticated approaches than were available in years past. A key challenge remains, however, in that future indicators that are truly predictive may not fit an organization’s mindset and could be misread or ignored.

A telling historical example of this occurred on Dec. 7, 1941, when the captain of a submarine sailing back to port heard the sound of muffled explosions onshore. He turned to his lieutenant commander on deck and said, “I guess they are blasting the new road from Pearl Harbor to Honolulu.” The captain interpreted the explosions from his peacetime frame of reference, failing to recognize that an epic war between the United States and Japan had just started, with planes attacking the naval base at Pearl Harbor.

An even deeper psychological problem in proper monitoring, beyond inadvertently misinterpreting new information, is willful blindness. This happens when alarming warning signals are semi-unconsciously suppressed, distorted, or ignored to avoid addressing unwelcome realities.6

To guard against such oversights, the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) — which supplies non-weaponry materials to the U.S. armed forces globally — implemented a strategic radar to enhance its peripheral vision.7 This radar picked up weak signals of a slowdown in commercial radio frequency identification (RFID) deployments, which allowed DLA to adjust its global logistics strategies sooner.

Sometimes signals that do not fit any of the scenarios add the greatest strategic value because they suggest that the scenarios themselves may need revision. For example, Shell and many other organizations and leaders, including the Pentagon and former Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev, failed to anticipate the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. A full analysis of aberrant signals that collectively do not fit any of the official scenarios might actually provide a timely wake-up call.

4. Improve organizational agility. A complement to scenario planning, agility is the ability to mitigate unanticipated disruptions and seize short-lived opportunities expeditiously. Different contexts often require different approaches to building agility in advance. Adjusting operational plans is much easier than adapting organizational infrastructures; acting alone may be easier for an organization than leading strategic partners to move jointly, which in turn may be easier than orchestrating an entire ecosystem.8 We have studied different types of strategic agility in supply chains and found that these vary significantly in terms of the focus of the organization’s response (operational versus systemic) and the strategic actors involved

(just the company, a partnership, or an entire network/ecosystem). They also vary according to the speed of response and the magnitude of change required. The common theme in all cases we examined was that organizational agility allowed leaders to respond effectively to micro surprises, while scenario planning focused on macro shifts in the environment.

A telling example of organizational agility is how some companies handled critical port logjams in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit most companies unexpectedly.9 While more than a hundred container ships waited to dock at ports in Los Angeles and Long Beach, California, some agile companies chartered private cargo ships to import products manufactured in Asia via alternative ports. And some other companies were able to source products from new suppliers in Mexico via land transport.

5. Foster decision-making savvy. Timely and accurate information is needed to track whether the strategy needs fine-tuning, whether key strategic options should be exercised, and if the scenarios themselves are still valid. The organization’s structure directly affects what information is collected, where it flows, and who makes what decisions. Information and decision-making are what connect the organization’s design to the micro aspects of how projects are managed day to day within the enterprise. A key question is whether managers are sufficiently aware of common decision traps when dealing with uncertainty, including biases such as overconfidence, myopic framing, anchoring, or groupthink.10 Likewise, organizations should consider whether there are training programs in place to teach employees how to manage uncertainty better at both the strategic and operational levels, either alone or in teams.

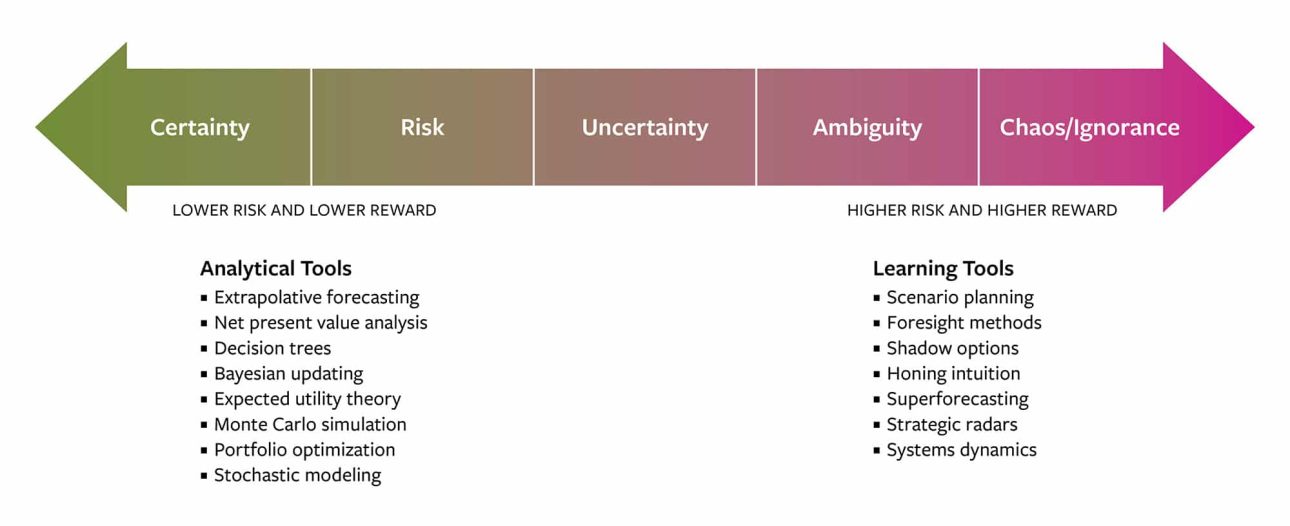

The figure “Scenario Planners’ Toolkit” lists numerous tools that managers typically have available, depending on how well they understand the issues at hand. The spectrum of understanding ranges from near certainty, to knowable risk (when probabilities are available), to uncertainty (when outcomes can be assessed but not probabilities), to ambiguity (the problem is not well understood), and, finally, to chaos (when little is known and managers lack experience). As knowledge and understanding diminish, managers may increasingly feel like they are getting lost in the woods. But often, it is the territory described on the right side of the diagram where the richest new opportunities lurk (as well as the biggest risks).11 Dealing with ambiguity and chaos demands an emphasis on learning and challenging mental models rather than on optimizing quantitative models.

Scenario Planners’ Toolkit

Familiar managerial tools can help clarify issues where there is a higher degree of certainty. Where managers are on unfamiliar ground, tools such as scenario planning and real-options analysis are more useful for decision-making.

In circumstances where managers have limited knowledge, honed intuition can be especially valuable because it allows them to draw on past experiences while also being creative. Scenario thinking can help here, since it primes people to see the world kaleidoscopically and notice things that otherwise might have been ignored.12 If done well, scenarios build a “memory of the future,” like a wedding rehearsal does, so that future changes become easier to recognize. Broader business challenges about which much is unknown typically require deeper questions about assumptions, incomplete information, problem framing, and mental models. The challenge is to acknowledge collective ignorance and to try to learn faster than rivals, rather than optimizing tightly structured, static problems that may prove, in hindsight, to have been poorly framed.

The earlier DLA example of developing a strategic radar demonstrates one way to improve decision savvy.13 Once a quarter, 15 experts would evaluate the relevance of about 20 signals collected in five different categories. The full list of about 100 signals would then be shortened to the 20 to 30 most relevant ones and debated further by experts and managers. DLA also used web-based dashboards to visualize external changes and alert leaders when some strategic or tactical decisions needed to be revised.14

6. Cultivate strong leadership. Leaders play critical roles in helping organizations navigate uncertain waters on two separate fronts. First, like a calm captain amid a nasty storm, leaders are the final buffers against uncertainty. They absorb the initial shock, help create meaning, and rekindle hope for those who are befuddled. Since not all uncertainties can be anticipated or trained for, leaders must remain willing and visible bearers of the company’s residual uncertainty. Second, they need to have a tolerance for ambiguity and an ability to engage in rapid sensemaking when crises occur. This requires experience, intellect, fortitude, and a degree of preparedness that can be honed by tools such as scenario planning, role-playing, and simulation. A key aspect is that leaders must try to anticipate if and when a change in strategy is needed.

The British Armed Forces deployed its famous red teams to accomplish this. The red team’s main mission is to collect any disconcerting information about the current plan and then synthesize all of it so that leaders can decide whether to change course.15 In essence, the red team is asked to play the role of the loyal opposition to the current plan.

Since not all uncertainties can be anticipated or trained for, leaders must remain willing and visible bearers of the company’s residual uncertainty.

Building tolerance for ambiguity, encouraging evidence-gathering, and surfacing doubts about key assumptions before charging ahead requires a systematic approach. Employees’ attitudes toward uncertainty, for example, often do not match those of the organization’s leaders.16 As Paul’s research with George Day suggests, leaders must orchestrate an enterprisewide approach to developing organizational vigilance.17 This starts with a strong leadership commitment to being comfortable with uncertainty and exploring weak signals from credible sources; investing in foresight capabilities (like scenario planning, warning signals, and links to innovation hubs or venture teams); adopting flexible strategy-making processes that examine external uncertainties all around; and improving accountability and coordination at multiple organizational levels, within functions and enterprisewide.

Visionary leadership is what helped Alchemy launch a scenario-planning project that successfully proceeded from design through implementation.18 This multiparty effort involved the supply chain leaders of 18 business units plus various functional heads, covering 13 countries. The scenarios were developed by interviewing global and regional leaders and examining over 200 documents about changing business environments. This collective effort resulted in a flexible supply chain strategy, with diverse stakeholders aligning around shared objectives. The key challenge was to transcend the short-term orientations of operational supply chain managers through discussion, broader visions, and trust-building.

Better Approaches to Uncertainty

As uncertainty continues to increase in business, leaders should rethink how they handle it. The first step is to be intellectually honest about how much can be predicted about the future and what is truly unknowable now. Next, leaders should review to what extent their organization currently relies on each of the six practices discussed above. They may also want to explore more deeply how to integrate the various practices to benefit from their potential synergies. Leaders could even elevate them to core competencies, as Shell did in the 1980s with scenario planning. If properly designed, these practices will function in harmony as a synergistic metasystem for decision-making under uncertainty. If done well, scenario planning will help surface the smartest adaptive strategies, the best indicators to monitor, and how to interpret weak signals. Also, exercising the right options embedded in flexible strategies requires monitoring data in real time. Above all, without strong leadership and the right culture, an organization may not be sufficiently agile when turbulence strikes.

Too many leaders today still view uncertainty as an unwelcome intrusion into well-laid plans for achieving smooth operations and predictable financial results. The rigid tyranny of budgets, tight performance goals, and incessant earnings scrutiny has turned uncertainty into an enemy. But without uncertainty, many companies and industries — from trading to insurance to biotech — would not exist in their current form or at all. When asked about uncertainty, Intel CEO Andy Grove replied, “Give me a turbulent world as compared with a stable world and I’ll want the turbulent world,” epitomizing the entrepreneurial spirit.19 This attitude also means, however, that leaders must know how to navigate uncertainty for its upside while also protecting against its downside. Scenario planning and the five other levers in our model provide an especially effective toolkit to manage this enduring challenge in the face of uncertainty.

References

1. P.J.H. Schoemaker, “Scenario Planning: A Tool for Strategic Thinking,” Sloan Management Review 36, no. 2 (winter 1995): 25-40.

2. P.J.H. Schoemaker and C.A.J.M. van der Heijden, “Integrating Scenarios Into Strategic Planning at Royal Dutch/Shell,” Planning Review 20, no. 3 (May/June 1992): 41-46, https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(93)90324-9.

3. For details, see C. Loh and P. Pande, “What Are ETOPS Rules and Why Do They Matter?” Sept. 14, 2023, https://simpleflying.com.

4. S.S. Phadnis and I.-L. Darkow, “Scenario Planning as a Strategy Process to Foster Supply Chain Adaptability: Theoretical Framework and Longitudinal Case,” Futures & Foresight Science 3, no. 2 (June 2021): 1-14, https://doi.org/10.1002/ffo2.62.

5. S.S. Phadnis, C. Caplice, Y. Sheffi, et al., “Effect of Scenario Planning on Field Experts’ Judgment of Long-Range Investment Decisions,” Strategic Management Journal 36, no. 9 (September 2015): 1401-1411, https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2293.

6. M. Heffernan, “Willful Blindness: Why We Ignore the Obvious at Our Peril” (Walker, 2011); see also M. Heffernan, “Uncharted: How to Navigate the Future” (Avid Reader Press, 2020).

7. P.J.H. Schoemaker, G.S. Day, and S.A. Snyder, “Integrating Organizational Networks, Weak Signals, Strategic Radars and Scenario Planning,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 80, no. 4 (May 2013): 815-824, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.10.020.

8. S.S. Phadnis and P.J.H. Schoemaker, “Strategic Agility in Supply Chains: A Conceptual Research Review,” Strategic Management Review, forthcoming.

9. S.S. Phadnis and P.J.H. Schoemaker, “Visibility Isn’t Enough: Supply Chains Also Need Vigilance,” Management and Business Review 2, no. 2 (spring 2022): 49-59, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4417573.

10. J.E. Russo and P.J.H. Schoemaker, “Winning Decisions: Getting It Right the First Time” (Doubleday, 2001).

11. For a fuller treatment, see P.J.H. Schoemaker, “Profiting From Uncertainty” (Free Press, 2002), as well as P.G. Clampitt and R.J. DeKoch, “Embracing Uncertainty: The Essence of Leadership” (Routledge, 2001).

12. G. Klein, “Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions” (MIT Press, 1998); also see R.M. Hogarth, “Educating Intuition” (University of Chicago Press, 2001). Intuition received a popular boost thanks to Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking” (Little, Brown, 2005). For a critical review of that book, see R.S. Hogarth and P.J.H. Schoemaker, review of “Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking,” by M. Gladwell, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 18, no. 4 (October 2005): 305-309, https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.497.

13. G.S. Day, P.J.H. Schoemaker, and S.A. Snyder, “Extended Intelligence Networks: Minding and Mining the Periphery,” ch. 16 in “The Network Challenge: Strategy, Profit and Risk in an Interlinked World,” eds. P.R. Kleindorfer and Y. Wind (Wharton School Publishing, 2009).

14. For specifics, see S.A. Snyder and P.J.H. Schoemaker, “Strategic Radar: Scenario-Based Monitoring and Scanning to Sense and Adapt to External Signals,” ch. 3 in “Building Strategic Concepts for the Intelligence Enterprise” (Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 2009).

15. Personal communication between Paul Schoemaker and Sir Kevin Tebbit, former permanent secretary of the U.K. Armed Forces; also see P. Bose, “Alexander the Great’s Art of Strategy: The Timeless Lessons of History’s Greatest Empire Builder” (Gotham, 2003).

16. Clampitt and DeKoch, “Embracing Uncertainty.”

17. P.J.H. Schoemaker and G. Day, “Preparing Organizations for Greater Turbulence,” California Management Review 63, no. 4 (August 2021): 66-88, https://doi.org/10.1177/00081256211022039.

18. Phadnis and Darkow, “Scenario Planning as a Strategy Process.”

19. R. Karlgaard and G. Gilder, “Talking With Intel’s Andy Grove,” Forbes, Feb. 26, 1996, 63.