Why Robots Will Displace Managers — and Create Other Jobs

While robot-adopting companies may shed some management and middle-skilled jobs, research shows that robots will increase employee head counts overall.

News

- Bitcoin Set for First Yearly Loss Since 2022 as Macro Pressures Weigh on Crypto

- As AI Ambitions Grow, Tech Leaders Look Beyond Earth for Data Infrastructure

- OpenAI Rebuilds Around Audio in Push Toward Voice-First AI

- DeepSeek Signals Next AI Model Direction With New Training Research

- “The Feed Is Dead” in the Age of AI, Says Instagram CEO

- NVIDIA Deepens AI Push With $5 Bn Intel Stake, $20 Bn Groq Deal

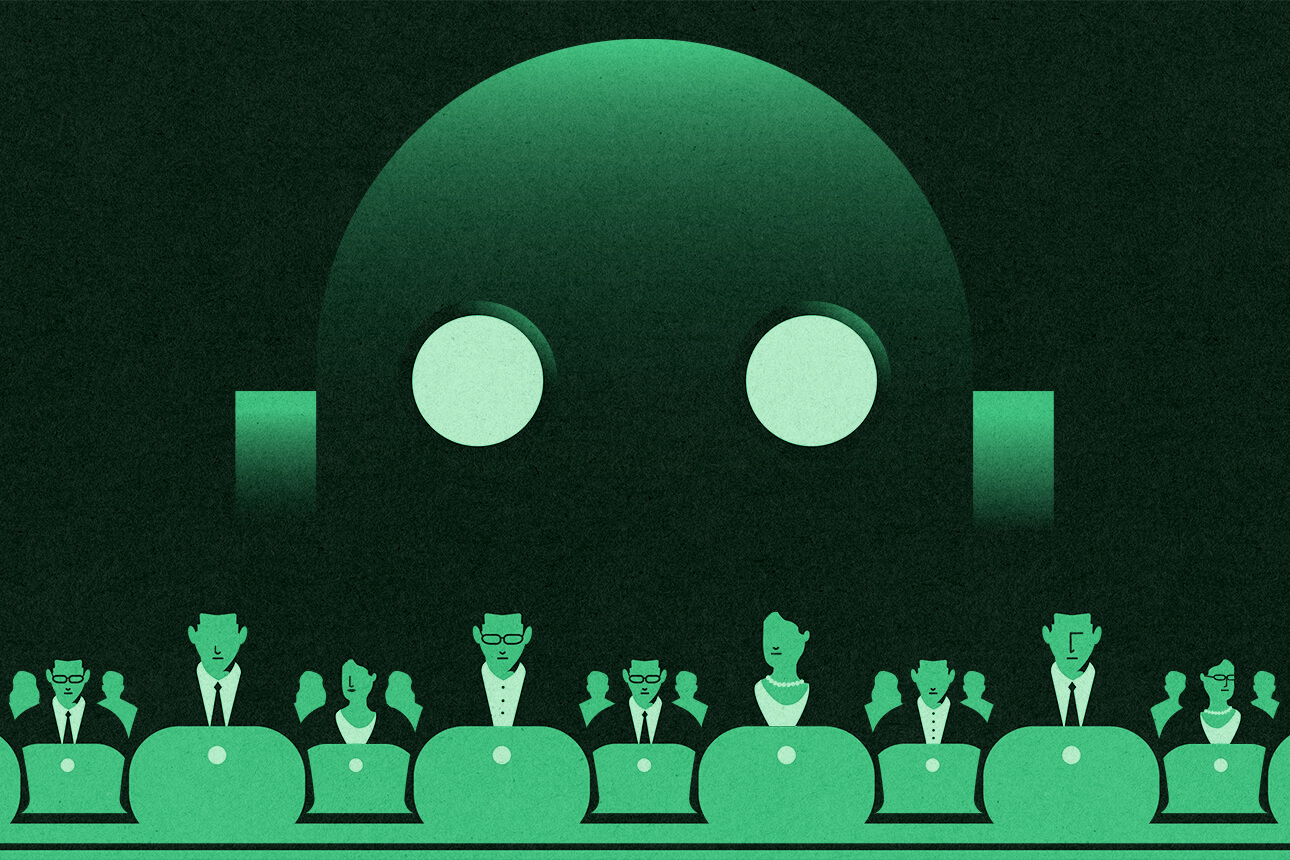

Carolyn Geason-Beissel/MIT SMR | Getty Images

RECENT, DRAMATIC GROWTH in robot adoption across an increasing number of global industries has sparked avid interest in the impact robots will have in the workplace — particularly which jobs they will replace and whether any new jobs will be created for humans.1 Our recent research focused primarily on physical robots, including both industrial and collaborative robots, used in production processes. Our data confirms that companies are indeed eliminating some human jobs in favor of robots — but that robot adoption is increasing the total number of nonmanagerial employees while reducing the number of middle managers needed.2

Even with rapid technological advancements, robots aren’t yet capable of managing human employees. So why are managerial positions being eliminated when the robots arrive? Our research highlights two significant changes robots bring to the workplace that can explain this shift. One is the radical transformation in managers’ ability to measure and reward the performance of individual employees who work with robots. The other is a change in the skills required of nonmanagerial employees, which is affecting the nature of managerial work itself. When companies invest in robots, the combined effect of these two changes leads to reductions in managerial head count that can be dramatic.

How Efficiency Gains Impact Managers

In a previous MIT SMR article, we described how robot adoption is transforming organizations by making human performance measurement easier, thus enabling organizations to reward and manage talent more easily and effectively.

Managers expend a significant amount of effort on people management — almost a third of their time, according to a recent McKinsey survey. When work is primarily done in teams, each individual employee’s contribution to group performance can be hard to discern.3 But robot adoption reduces the amount of time and effort required to compare individuals’ productivity levels, in many cases substantially so. This can be explained by a simple stylized example: If two humans work with the same type of robot but their levels of productivity differ, the consistency and transparency of the robot’s performance when working with both employees allows a manager to more easily observe the contribution of each person in isolation. With more precise robot-enabled performance data, organizations are able to better reward their best-performing employees, with many companies adopting bonus incentives directly tied to individual (rather than team or company) performance.

Improved performance management doesn’t mean that talent management is no longer necessary or that managers aren’t needed; instead, this more accurate performance measurement enabled by robots makes supervisors much more efficient at managing employee performance. The manager who previously may have been able to manage only five employees can now effectively manage a larger team. (While the increase in team size varies by company and its investment in robot adoption, our analysis showed that $1 million in robot investment led to a span-of-control increase of roughly five employees.) As a consequence, fewer managers are needed in the robot-adopting organization.

A Change in Skill Needs

Robot adoption can also change the employee roles that organizations need. In our research, we found that robots led to significant reductions in middle-skilled employees, such as machinists, welders, and other assembly-line workers, whose roles require vocational or trade school education. Robots are able to do the same tasks with much greater consistency and precision than human workers and have become increasingly cost-effective.

However, we also found that companies that invest in robots significantly increase hiring for both high- and low-skilled jobs, outweighing the loss of middle-skilled jobs within the organization. The increase in high-skilled jobs that require at least a bachelor’s degree is mainly driven by the need for humans to manage the robots themselves, performing tasks such as programming and design. The increase in low-skilled jobs that require, at most, a high school education is driven by the need for human labor to do the tasks that robots are not yet able to do effectively. Amazon, for example, still depends on a large human workforce to load and operate its delivery vans. Despite substantial investments and advances in the technology, these tasks still remain difficult for robots to reliably perform.

When companies invest in robots, significantly fewer middle managers are ultimately needed. Dramatic shifts in workforce composition have, in turn, changed what organizations need from their managers. Low-skilled work is typically more standardized and consequently easier to monitor and evaluate, reducing the need for a higher managerial head count.4 Managing low-skilled professionals primarily involves monitoring work procedures and output, issuing commands, and ensuring that workers do their job properly.5 Given that high-skilled workers are often the experts in dealing with nonroutine problems and can frequently resolve them better than their managers could, managing these employees often requires fewer direct commands and a greater emphasis on advising and empowering workers to solve problems.6

Middle Managers’ Unique Skills

Middle managers play a crucial role in helping organizations navigate technological changes and their corresponding organizational changes, since they remain responsible for implementing the C-suite initiatives that will enable their company to maintain competitive advantage. These managers must adopt new technologies effectively and integrate them into existing operations.

For example, Stanley Black & Decker replaced humans with robots to inspect its tape production process and detect production errors. Managers’ soon discovered that robot-collected data about inspection errors could be analyzed to identify patterns and highlight upstream production issues. After Stanley Black & Decker’s upstream production processes were modified, the company was able to prevent such errors. Notably, both the discovery of the analytics opportunity and the subsequent process improvements were the result of middle managers’ expertise and efforts: They were uniquely positioned to see the upstream and downstream processes. Neither the C-suite executives nor nonmanagerial employees at the company would have been able to clearly discern the opportunity for improvement or to implement the necessary changes.

Widespread robot adoption is dramatically changing the workplace, including eliminating human jobs — but robot adoption won’t have the same impact on every role. Although robots are not yet capable of managing humans, our research reveals that robot adoption changes managerial responsibilities, enabling a reduction in the number of managers needed and redefining the role of middle management. Companies that understand and effectively navigate these changes will benefit the most from the robot revolution.

References

1. D. Acemoglu, D. Autor, J. Hazell, et al., “Artificial Intelligence and Jobs: Evidence from Online Vacancies,” Journal of Labor Economics 40, no. S1 (April 2022): S293-S340; E. Brynjolfsson, W. Jin, and K. McElheran, “The Power of Prediction: Predictive Analytics, Workplace Complements, and Business Performance,” Business Economics 56, no. 4 (October 2021): 217-239; K. Eggleston, Y.S. Lee, and T. Iizuka, “Robots and Labor in the Service Sector: Evidence From Nursing Homes,” working paper 28322, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts, January 2021; and A. Stahl, “Will ChatGPT Replace Your Job?” Forbes, March 3, 2023, www.forbes.com.

2. J. Dixon, B. Hong, and L. Wu, “The Robot Revolution: Managerial and Employment Consequences for Firms,” Management Science 67, no. 9 (September 2021): 5586-5605.

3. A.A. Alchian and H. Demsetz, “Production, Information Costs, and Economic Organization,” The American Economic Review 62, no. 5 (December 1972): 777-795.

4. C. Perrow, “A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Organizations,” American Sociological Review 32, no. 2 (April 1967): 194-208.

5. J.P. MacDuffie, “The Road to ‘Root Cause’: Shop-Floor Problem-Solving at Three Auto Assembly Plants,” Management Science 43, no. 4 (April1997): 479-502; and S. Helper and R. Henderson, “Management Practices, Relational Contracts, and the Decline of GeneralMotors,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28, no. 1 (winter 2014): 49-72.

6. S. Helper, J.P. MacDuffie, and C. Sabel, “Pragmatic Collaborations: Advancing Knowledge While Controlling Opportunism,” Industrial and Corporate Change 9, no. 3 (September 2000): 443-488; M. Kenny and R. Florida, “Beyond Mass Production: The Japanese System and Its Transfer to the U.S.” (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); H. Mintzberg, “The Nature of Managerial Work” (New York: Harper & Row, 1973); and H. Mintzberg, “Simply Managing: What Managers Do — and Can Do Better” (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2013).